|

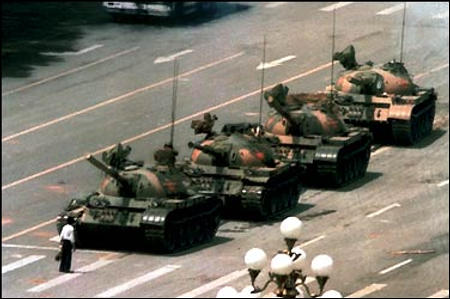

| Can revolutionaries bring change without imitating the oppression forced upon them? http://goo.gl/2Bj5k |

Marx’s theory of historical materialism

rests on an indefensible economic reductionism. Critically evaluate.

In The

Communist Manifesto, Marx argues that ‘the charges against communism made

from a religious, a philosophical and, generally, from an ideological

standpoint, are not deserving of serious examination’ (Marx,

Engels, & Moore, 1998, p. 18). In this essay

I will argue that many of these criticisms of Marxist style political and

economic communism are deserving of serious examination. First, the

terms ‘materialism’ and ‘economic reductionism will be examined’. Second, a

brief overview of Marx’s thoughts in regard to the question will take place.

The problems surrounding economic reductionism, materialism, and the inevitable

violent outcomes of these theories will then be discussed.

According to the

Routledge encyclopaedia of philosophy, materialism is ‘a set of related

theories which hold that all entities and processes are composed of – or are

reducible to – matter, material forces or physical processes.’ Furthermore, ‘Materialism

entails the denial of the reality of spiritual beings, consciousness and mental

or psychic states or processes, as ontologically distinct from, or independent

of, material changes or processes’ (Wood,

1998).

Materialism provides an exact scientific basis to life. For Marx, materialism

is able to explain descriptive phenomena, providing a basis of history. From

this basis of history, through its epochs and revolutions, patterns emerge. These

patterns, from a materialist setting, emerge due to the economic relations of

society. Marx’s theory is better understood as deterministic or fatalist rather

than prescriptive or moral (Croce,

1966, p. xi). According to Marx, the economic

sphere is ‘the real foundation of society’ and therefore, ‘labour is the

essence of humanity’ (Hughes,

2007, p. 67; Marx & Engels, 1968, p. 182). The suggestion

that economic science is the basis of society leads to economic reductionism,

which is the natural outcome of materialism.

Economic

reductionism, which stands at the centre of Marx’s thought, is laced with

problems. Marx perceives a broad range of issues in society which through

scientific historical analysis he explains the economic epochs which human societies

have weaved through. He expresses strong concern in regard to the oppression of

the proletariat (the working class) throughout his work, while voicing an equal

degree of contempt for the middle-class bourgeoisie. As Dupré aptly summarises

in The Philosophical Foundations of Marxism, Marx’s chief concern is

that ‘those who contribute most to the production receive the least enjoyment

from the actual product’ (Dupré,

1966, p. 149). Marx expresses further contempt

for the bourgeoisie in The Communist Manifesto by stating that they have

‘agglomerated population, centralised means of production, and has [sic] concentrated

property in a few hands’ (Marx

et al., 1998, p. 7). He also expresses concern for

child labour on multiple occasions (Marx

et al., 1998, pp. 17, 20). Marx is not

specifically concerned with the immorality or metaphysics of oppression, but

rather, his concern regarding oppression is in relation to the progression of

history. While referring to the phenomena as a struggle between proletarians

and bourgeoisies, he also implies that the transition to communism is part of

the unfolding development of human history. It seems that while with one hand

Marx denies morality as a facade for religion through showing its

incompatibility with materialism, with the other hand, he employs morality into

his discourse with moral prescriptions and ethical assessments.

In The Communist Manifesto, Marx

writes that ‘the theoretical conclusions of the Communists are in no way based

on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered, by this or that

would-be universal reformer. They merely express, in general terms, actual

relations springing from an existing class struggle, from a historical movement

going on under our very eyes’ (Marx

et al., 1998, pp. 13–14). He uses a

bottom-up materialist approach rather than a top-down spiritual understanding

of the world (Dupré,

1966, p. 155). This has strong implications for

any theorist, philosopher, or theologian who may suggest that meaning can be

derived from outside the economic sphere. As one writer suggests, ‘any

interpretation that sought to detect aesthetic and ethical elements of Marx’s

thought must address his critique of ideology and his apparent reductionism in

viewing the ‘superstructure’ as simply determined by the economic-material

base’ (Hughes,

2007, p. 64). Marx’s reductionism denies the

moral and philosophical realm, retendering it ‘not deserving of serious

examination’, which begs the question, ‘what is one to do according to Marxist

law?’ Should one stand aside from the unfolding of history, or perhaps, try to

speed its progress?

It is clear that Marx suggests that

there is some kind of moral imperative in his theory. Marx concludes The

Communist Manifesto by stating, ‘the proletarians have nothing to lose but

their chains. They have a world to win. Workingmen of all countries, unite!’ (Marx

et al., 1998, p. 30). His conclusion draws out two

problems, the first is conceptual while the second is practical. The conceptual problem is that Marx gets an

‘ought’ from an ‘is’, and moreover, from an ‘is’ that is entirely based on a

materialist conception of history. It is difficult to predict the trajectory of

history, and even more problematic to understand morality in terms of economics

and history alone. Hypothetically, if the next stage of history was the further

oppression of the working people, the exploitation of the environment, and the

extinction of various animal species; it would be difficult to tell what Marx’s

moral prescriptions would be. It seems to be of pure coincidence that Marx’s

next stage of history, when the proletarians violently overthrow the

bourgeoisie, happens to synthesise with some conceptions of morality. As for

the practical refutation of encouraging ‘workingmen of all countries’ to

‘unite’, it is interesting to note that there is no longer a clear division

between the proletarians and the bourgeoisie, meaning that no longer are proletarians

across the world united in struggle (Milanovic,

2011, pp. 110–111). Revolution seems less likely as

the proletarians become more comfortable. Poverty was once driven by class, but

it is now ‘almost entirely driven by location’ according to Milanovic (2011,

pp. 112–113). Poverty in developing countries

calls for a revolution of kinds, yet Marx seems to make no prescriptions here. It

is ironic that workers in country A who are wealthier than the bourgeoisie in

country B, must be equally concerned with political change in their own midst

as they should be with the lot of the workers in country B who are much

worse-off than they are. According to strict Marxist thought, modern

understandings of poverty and development are irrelevant. The famine stricken

Somali villagers must form unions and violently overthrow the classes who hold

them back. If ‘man’s essence depends on his productive activity, and this

activity is determined by nature’, then it seems that we will be led to these

illogical conclusions (Dupré,

1966, p. 148).

It is interesting that Marx seems

to support the intrinsic value of the human being. He wants to abolish the

‘miserable character of this appropriation, under which the labourer lives

merely to increase capital’ (Marx

et al., 1998, p. 15). Marx also voices his opinion

against children being ‘transformed into simple articles of commerce and instruments

of labour’ (my

emphasis, Marx et al., 1998, p. 17). While I side

with Marx’s concern, it is philosophically problematic for Marx to accept the

concept of intrinsic value while simultaneously being a firm supporter of

historical materialism and economic reductionism. It is understandable that

Marx attempts to integrate a Kantian understanding that it is inappropriate to

use another person as a ‘mere means’ to generate ecumenical appeal, however, to

argue that children should not be ‘transformed into simple articles of commerce

and instruments of labour’ presupposes that there is another basis to the value

of humans that is neither economic nor material. If there was child labour

intended to help the working class, it would seem that Marx could not take

issue with it.

In the final section of this paper, the issue

of Marx’s prescriptions, especially those in relation to violence, will be

discussed. Marx suggests in The Communist Manifesto that ‘the violent

overthrow of the bourgeoisie lays the foundation for the sway of the

proletariat’, and later that the Communists ‘openly declare that their ends can

be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions’ (Marx

et al., 1998, pp. 12, 30). He also

suggests that the ‘overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy’ and the ‘ conquest of

political power by the proletariat’ is part of the ‘immediate aim’ of (Marx’s

version) of communism (Marx

et al., 1998, p. 13). Croce articulately discerns that

an action ‘may have economic value without being moral, and the consideration

of economic value must therefore be independent of ethics’ (Croce,

1966, p. xvi). Therefore, the ultimate problem

of Marx’s theory is that it cannot care whether an action is moral, but only

whether an action has economic value. Leo Tolstoy argues that the means of

socialist revolution are ‘in the first place and above all, immoral, containing

falsehood, deception, violence, murder; in the second place, these means can in

no case attain their end’ (Tolstoy & Stephens, 1990, p. 62). Tolstoy gives

a two part criticism to socialist revolutionary theories of change. The first

part pertains to the means being ‘immoral’. This will be considered as the

philosophical distinction. The second part of Tolstoy’s criticism relates to

the means being unable to achieve their desired ends. This will be considered

as the pragmatic distinction. Both Tolstoy’s philosophical and pragmatic

distinctions are powerful criticisms of Marx’s prescriptive thought.

Tolstoy shares Marx’s concern for

the working class and the oppressed. He writes that the ‘men of the ruling

classes, who have no reasonable explanation of their privileges, and who in

order to retain them are forced to repress all their nobler and more humane

tendencies, try to persuade themselves of the necessity of their superior

position; while the lower classes, stultified and oppressed by labour, are kept

by the higher classes in a state of constant subjection’ (Tolstoy, 2009, p. 284). Tolstoy hears

the cries of the oppressed, and while he is committed to pacifism, he is not

committed to being passive. He suggests that the people should cease to support

the army, a body of working class people who have been convinced to repress their

working class peers in the interests of the wealthy (Tolstoy

& Stephens, 1990, pp. 61–63). Tolstoy argues

that if power, or the current structures of its manifestations, are to be

abolished it must be abolished not by force but by man’s awareness of its lack

of utility and intrinsic evil. When men refuse to join the army and refuse to

pay taxes the foundations of the current order will crumble. Tolstoy’s

conception of nonviolent social change rests on the premise that there is some

degree of humanity to be found in the so-called evil oppressors. He suggests

that ‘our wealthy classes, whether their consciences be tender or hardened,

cannot enjoy the advantages they have wrung from the poor, as did the ancients,

who were convinced of the justice of their position. All the pleasures of life

are poisoned either by remorse or fear’ (Tolstoy,

2009, p. 108). Therefore, it would be better for

one to suffer than to oppress, as living a moral life, according to Tolstoy, is

of far more value than imitating one’s oppressor. Tolstoy’s thoughts paved the

way for the struggle for independence in India as a practical alternative to

civil war. Gandhi described himself as ‘Tolstoy’s devoted follower’ and said

that Tolstoy’s writings ‘overwhelmed’ him (Lavrin,

1960, pp. 132–134). As Tolstoy suggested, and as

Gandhi proved, non-violent revolutions are possible and they also have greater

chances of success than violent revolutions, which contradicts Marx’s thoughts.

Peace and Conflict researcher Stephen Zunes suggests that ‘less destructive

means can be found to overcome dictatorial regimes and unjust social systems’.

He cites Iran, Bolivia, Sudan, Haiti, Philippines, Mali, and Madagascar as

nations who have been able to overthrow oppressive states through non-violent

action. Non-violent action in South Korea, Chile, Mongolia, Nepal, Bangladesh,

and Kenya has also led to some reforms (Zunes,

1994, p. 405). While Marx would cast away the

idea of a non-violent proletariat revolution as an idea that is merely religion

in disguise, the tangible evidence of non-violent revolutions not only being

moral but being more effective in achieving their ends is problematic for

Marx’s narrow path to freedom.

Marx’s historical materialism and economic

reductionism inevitably leads to the imperative for the proletariat to

violently revolt against the powers that be. The narrow reductionism and

materialism purported by Marx presupposes that the essence of man is his

productive capacity, ignoring any other realm of influence. While his concern

about the poor, property ownership, and the idle bourgeois is justified, his

solutions are dangerous, immoral, and ineffective at achieving their ends.

Bibliography

Croce, B. (1966). Historical materialism and the

economics of Karl Marx. London: Cass.

Dupré, L. K. (1966). The

philosophical foundations of Marxism. New York: Harcourt, Brace &

World.

Hughes, J. (2007). The

end of work : theological critiques of capitalism. Malden, MA: Blackwell

Publishing.

Lavrin, J. (1960).

Tolstoy and Gandhi. Russian Review, 19(2), 132–139.

doi:10.2307/126735

Marx, K., & Engels,

F. (1968). Selected works : in one volume. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Marx, K., Engels, F.,

& Moore, S. (1998). The Communist manifesto. London: Merlin Press.

Milanovic, B. (2011). The

haves and the have-nots : a brief and idiosyncratic history of global

inequality. New York: Basic Books.

Tolstoy, L. (2009). The

Kingdom Of God Is Within You. Guildford: White Crow Books.

Tolstoy, L., &

Stephens, D. (1990). Government is violence : essays on anarchism and

pacifism. London: Phoenix Press.

Wood, A. W. (1998).

Dialectical Materialism. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Routledge. Retrieved from http://www.rep.routledge.com/article/N013

Zunes, S. (1994).

Unarmed Insurrections against Authoritarian Governments in the Third World: A

New Kind of Revolution. Third World Quarterly, 15(3), 403–426.